Climate Variability and the Dawn of Agriculture: New Insights from the Zagros Mountains

A Stalagmite Record Reveals How Environmental Instability Shaped Early Neolithic Communities in the Fertile Crescent

The Fertile Crescent, a boomerang-shaped region stretching from the Nile Valley through the Levant to Mesopotamia, holds a unique place in human history as the birthplace of agriculture and civilization. Yet despite its significance, scientists have long struggled to understand precisely how climate influenced the transition from mobile hunter-gatherer societies to settled agricultural communities during the critical period between the Last Glacial Maximum and the Early Holocene.

A groundbreaking study published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences presents high-resolution paleoclimatic data from a stalagmite in the Kurdistan Region of Iraq, spanning 18,000 to 7,500 years ago. This research, led by Dr. Eleonora Regattieri of Italy’s National Research Council (CNR-IGG) and Professor Andrea Zerboni of the University of Milan, provides unprecedented insight into the environmental conditions that shaped the Neolithic Revolution in one of its core regions.

The Archive Beneath: Stalagmites as Climate Records

Stalagmites are remarkable geological structures that form over thousands of years as rainwater percolates through soil and limestone bedrock, depositing calcite layers. Within these layers lie chemical signatures—isotopes of oxygen and carbon, along with trace elements like magnesium, barium, strontium, and zinc—that preserve detailed information about past temperatures, rainfall patterns, vegetation cover, and atmospheric conditions.

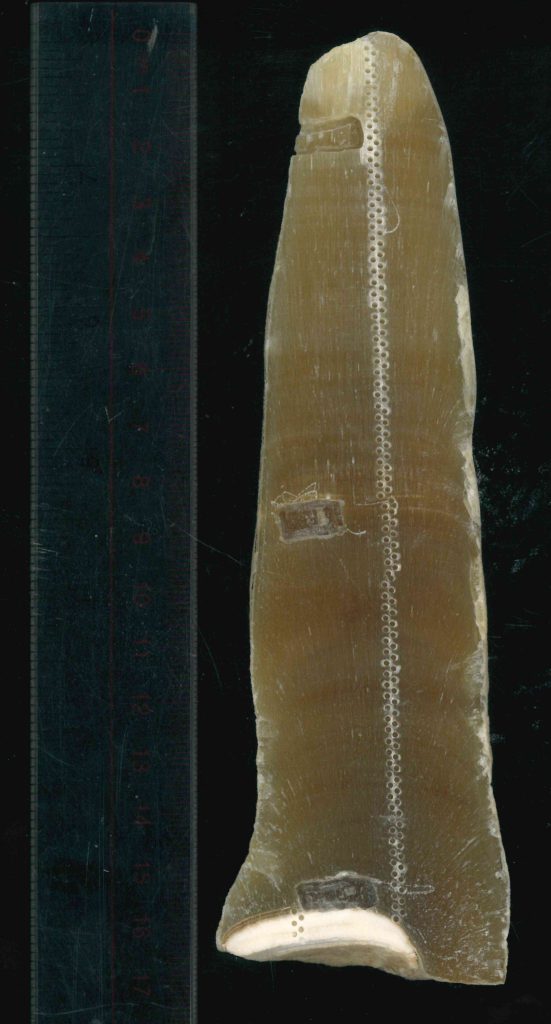

The stalagmite analyzed in this study, designated KR19-3, comes from Hsārok Cave in the northwestern Zagros foothills of Iraqi Kurdistan. This location is particularly significant because it sits at the heart of the Fertile Crescent, near tributaries of the Tigris River where some of humanity’s earliest civilizations flourished. The research team employed multiple analytical techniques including uranium-thorium dating, stable isotope analysis, and trace element measurements to reconstruct the region’s paleoenvironmental history with exceptional temporal precision.

A Period of Dramatic Climate Shifts

The study period encompasses one of the most climatically dynamic intervals in Earth’s recent history. The researchers identified several distinct climate phases that had profound implications for human communities:

The Last Glacial Maximum to Deglaciation (18,000-14,560 years ago)

During the Last Glacial Maximum, the stalagmite shows evidence of reduced precipitation and cooler temperatures, with oxygen-18 isotope values approximately 4‰ higher than during the Early Holocene. These conditions reflected both lower temperatures affecting water-calcite isotope fractionation and changes in the isotopic composition of moisture sources from the Mediterranean and Red Seas. Carbon isotope data indicates sparse vegetation and reduced soil biological productivity, painting a picture of a challenging environment for human habitation.

The Bølling-Allerød Warm Period (14,560-12,700 years ago)

Around 14,560 years ago, rainfall increased substantially in the region, leading to faster limestone deposition in the stalagmite. This wet phase coincided with global warming recorded in Greenland ice cores during the Bølling-Allerød interstadial. The oxygen isotope ratios decreased, indicating increased precipitation, while carbon isotope signatures revealed enhanced plant growth and soil biological activity.

However, the climate during this period was not simply wetter—it was highly variable. The record shows enhanced multidecadal hydroclimatic variability during the Bølling-Allerød chronozone, with frequent oscillations between wetter and drier conditions at timescales of decades to centuries. This variability had important implications for human adaptation strategies.

The Younger Dryas Cold Reversal (12,700-11,700 years ago)

Around 12,700 years ago, precipitation declined sharply and conditions became markedly dustier, as indicated by elevated concentrations of trace elements including barium, strontium, zinc, and sodium in the limestone layers. This abrupt shift corresponded to the Younger Dryas period, a mysterious global cooling event that particularly affected the North Atlantic region.

The Younger Dryas brought severe drought, intense dust storms, and reduced plant life to the Kurdistan region. The increased dust deposition, recorded through elevated trace element concentrations, suggests reduced vegetation cover and increased wind erosion—conditions that would have made the region significantly less hospitable for permanent settlements.

Early Holocene Stabilization (11,700-7,500 years ago)

Following the Younger Dryas, conditions gradually improved as the Earth entered the current interglacial period, the Holocene. Precipitation increased, temperatures rose, and the climate became more stable, creating favorable conditions for the development of agriculture and permanent settlements.

Sample of stalagmite KR19-3. Credit: Eleonora Regattieri

Synchronicity with Global Climate Patterns

One of the study’s most significant findings is the remarkable correspondence between local precipitation changes in the Zagros foothills and global temperature shifts recorded in Greenland ice cores. The record demonstrates that changes in local rainfall amount were coincident with changes in Greenland temperatures, revealing the global-scale teleconnections that influenced regional hydrology.

This synchronicity suggests that changes in North Atlantic circulation patterns and high-latitude ice sheet dynamics had direct and rapid impacts on precipitation regimes in the Middle East. The mechanisms likely involved shifts in atmospheric circulation patterns, storm tracks, and the position of the Intertropical Convergence Zone, which together modulated the delivery of moisture from the Mediterranean and Red Seas to the interior of the Fertile Crescent.

Regional Variations Across the Fertile Crescent

While the broad climate patterns were similar across the Fertile Crescent, the study reveals important regional differences. Comparison with regional paleoclimate data suggests similar precipitation patterns across the Fertile Crescent, but with greater hydroclimate variability during the Bølling-Allerød and drier conditions during the Younger Dryas in the eastern sector.

The eastern Fertile Crescent, encompassing the Zagros foothills and Mesopotamian plains, experienced more extreme climate variability than the western Mediterranean coastal areas. This gradient in climate stability had profound implications for the pace and character of the Neolithic transition in different regions.

Archaeological Correlations: Climate and Cultural Change

The paleoclimate record can be directly compared with archaeological evidence from nearby sites, revealing compelling connections between environmental change and human behavior. Palegawra Cave, located 140 kilometers from Hsārok Cave, was frequently occupied during summer in the initial warming phase as glaciers retreated, but was largely abandoned when the stalagmite indicates regional drying, with occupation resuming as conditions improved.

This pattern of occupation and abandonment closely tracks the climate shifts recorded in the stalagmite, suggesting that human communities were highly responsive to environmental conditions. During the unstable climate of the Bølling-Allerød and the harsh conditions of the Younger Dryas, permanent year-round settlements were not viable in the eastern Zagros foothills.

The Mobility Advantage: Environmental Variability as Cultural Catalyst

Rather than viewing climate instability solely as an obstacle to development, the research team proposes a more nuanced interpretation. The authors suggest that until the Holocene began, the Zagros foothills created a mosaic of spatially restricted yet resource-rich environments that were not suited to supporting large year-round settlements but encouraged mobility, allowing people to exploit seasonally available resources across different elevations and ecotones.

This environmental heterogeneity and temporal variability may have actually fostered important adaptive capacities. Communities developed sophisticated knowledge of multiple ecological zones—open woodlands, grasslands, and riparian habitats—and learned to move strategically to exploit seasonal resources. They cultivated flexibility, developed extensive social networks across regions, and accumulated diverse subsistence skills.

The researchers write that the strong climate variability during the Bølling-Allerød, together with the intrinsic ecological heterogeneity of the Zagros ecosystem, fostered cultural adaptations that would prove valuable when conditions eventually stabilized. When the climate became warmer and more predictable in the Early Holocene, these communities were well-positioned to experiment with plant cultivation and animal domestication, having already developed intimate knowledge of local plant and animal species through millennia of mobile foraging.

Divergent Neolithic Trajectories

The paleoclimate record helps explain a long-standing archaeological puzzle: why did the Neolithic transition occur at different times and in different ways across the Fertile Crescent? The extreme, unstable climate of the eastern Fertile Crescent meant people couldn’t rely on regular food supplies, which is likely why they remained mobile hunter-gatherers for longer than communities in the west.

Western regions of the Fertile Crescent, particularly the Mediterranean coastal zones, experienced less severe climate variability and avoided the worst impacts of the Younger Dryas drought. Archaeological evidence shows that settled villages with early forms of plant cultivation appeared earlier in these areas, before 11,000 years ago.

In contrast, the eastern Zagros region saw the full development of agricultural villages later, during the Early Holocene when climate conditions had stabilized. However, when agriculture did develop in these areas, it often incorporated a broader suite of domesticated crops and animals, potentially reflecting the diverse ecological knowledge accumulated during the preceding millennia of high mobility and environmental variability.

Broader Implications: Climate and the Neolithic Revolution

This research contributes to longstanding debates about the role of climate in the Neolithic Revolution. Earlier theories proposed simple cause-and-effect relationships, such as climate stress forcing innovation or improved conditions enabling population growth. The stalagmite record reveals a more complex reality.

Climate change did not uniformly drive or enable agricultural development across the Fertile Crescent. Instead, different climate trajectories in different regions created diverse selective pressures and opportunities. Communities responded with varying strategies appropriate to their local conditions, leading to multiple pathways toward agriculture rather than a single uniform transition.

The study also highlights the importance of climate variability, not just mean climate states. The multidecadal oscillations during the Bølling-Allerød may have been as significant as the long-term trends in shaping human adaptive strategies. Frequent environmental fluctuations selected for flexibility and knowledge diversity—traits that ultimately facilitated the transition to food production when conditions stabilized.

Methodological Significance: Caves as Climate Archives

Beyond its specific findings about the Fertile Crescent, this research demonstrates the exceptional value of speleothem records for paleoclimate reconstruction. The Hsārok Cave stalagmite provides consistent evidence across multiple proxies—carbon-13 to carbon-12 ratios revealing plant growth patterns that align with oxygen-16 and -18 ratios indicating temperature and moisture.

This internal consistency, combined with the stalagmite’s continuous formation over the critical transition period and its precise uranium-thorium dating, makes it an invaluable archive. Few other paleoclimate proxies can provide such high-resolution, well-dated, multi-proxy records from terrestrial environments in the Middle East.

The success of this study points to the potential for further speleothem research in the region. Kurdistan and the broader Zagros Mountains contain numerous caves that remain unexplored or inadequately studied. Additional stalagmite records could refine our understanding of spatial climate patterns, reveal higher-frequency climate oscillations, and extend the temporal coverage to include later periods of civilization development.

Contemporary Relevance: Lessons for the Present

While this research focuses on ancient climate and prehistoric societies, it carries important implications for understanding contemporary climate challenges in the Middle East. The region today faces significant environmental pressures including increasing temperatures, changing precipitation patterns, and water resource stress.

The paleoclimate record demonstrates that the Fertile Crescent has experienced dramatic climate variability in the past, with rapid shifts between wet and dry conditions. It also shows that human communities in the region have repeatedly demonstrated resilience and adaptability in the face of environmental change, though not without significant disruptions to settlement patterns and subsistence strategies.

Understanding how past communities navigated climate variability can inform modern adaptation strategies, though with the crucial caveat that contemporary climate change occurs in the context of much larger populations, intensive land use, and complex political and economic systems that differ fundamentally from Neolithic conditions.

Future Research Directions

This study opens several avenues for future investigation. Integration of additional paleoclimate records from diverse locations across the Fertile Crescent would provide a more complete spatial picture of climate gradients during the Neolithic transition. Higher-resolution archaeological excavations precisely dated using radiocarbon techniques could reveal more detailed correlations between specific climate events and cultural changes.

Paleobotanical and paleozoological studies could illuminate how plant and animal communities responded to the climate shifts recorded in the stalagmite, providing additional context for understanding human subsistence strategies. Genetic studies of domesticated crops and animals could potentially reveal whether climate variability influenced the tempo and geography of domestication processes.

Climate modeling studies could explore the atmospheric and oceanic dynamics that linked North Atlantic climate changes to Middle Eastern precipitation patterns, testing hypotheses about the teleconnection mechanisms suggested by the stalagmite-ice core correspondence.

Conclusion

The Hsārok Cave stalagmite provides a remarkable window into the environmental conditions that prevailed during humanity’s transition from hunting and gathering to agriculture in the Fertile Crescent. The record reveals a period of dramatic climate variability, with frequent oscillations between wetter and drier conditions culminating in the severe drought of the Younger Dryas period.

These findings illuminate why the Neolithic transition occurred differently in the eastern and western Fertile Crescent. In the Zagros foothills, climate instability delayed the development of permanent agricultural settlements but may have fostered adaptive flexibility that ultimately contributed to successful agricultural development when conditions stabilized in the Early Holocene.

The research demonstrates that climate-human interactions during the Neolithic Revolution were complex and regionally variable. Rather than climate deterministically driving cultural change, different environmental contexts created different selective pressures and opportunities, to which human communities responded with diverse and creative strategies.

As we face our own era of rapid climate change, this ancient record reminds us both of the challenges that environmental variability poses to human societies and of the remarkable capacity of human communities to adapt, innovate, and ultimately thrive in the face of changing conditions.

References

-

Regattieri, E., et al. (2025). A speleothem record from the Fertile Crescent covering the last deglaciation better contextualizes neolithization. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 122(50), e2502092122. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.2502092122

-

Regattieri, E., et al. (2023). Neolithic hydroclimatic change and water resources exploitation in the Fertile Crescent. Scientific Reports, 13, 45.

-

Asouti, E., et al. (2020). The Zagros epipalaeolithic revisited: New excavations and 14C dates from Palegawra cave in Iraqi Kurdistan. PLoS One, 15, e0239564.

-

Matthews, R., Matthews, W., Raheem, K. R., & Richardson, A. (Eds.). (2020). The Early Neolithic of the Eastern Fertile Crescent: Excavations at Bestansur and Shimshara, Iraqi Kurdistan. Oxbow Books.

-

Fleitmann, D., et al. (2025). Mid-holocene hydroclimatic optimum recorded in a stalagmite from Shalaii Cave, northern Iraq. Quaternary Science Reviews, 356, 109286.